Five Legendary Spinels

A popular cliché declares, ‘it is what it is’. This simple assertion, once named the ‘cliché of the year’, seems merely to state the obvious. In the case of the spinel, however, there’s something seriously wrong with this small bit of conventional wisdom.

Five legendary Rubies. These are not what they are. They are, in fact, spinels. Many of these “Titled Spinels” as they are known, have fascinating histories that go back thousands of years. From the Samarian Spinel that supposedly adorned the Golden Calf of the Israelites in the Sinai Desert, to an engraved Moghul Dynasties chronicle in the case of the Timur Ruby.

The most famous stone of all is the legendary Black Prince’s Ruby. Possibly one of the most illustrious gemstones in the entire world, this brilliant red spinel – which is the size of a chicken’s egg – is set in the middle of the British Imperial State Crown, illuminating the piece with a splendid fiery glow.

This epic 170-carat spinel made its first appearance on the world stage in the mid-14th-century as the possession of one Abu Said, a Moorish prince in Granada. Unfortunately for Abu Said, Prince Peter of Castile – called Don Pedro the Cruel – had heard about the jewel and wanted it for himself. Don Pedro invited Abu Said to Castile, allegedly to discuss a peace treaty. Instead, Pedro killed Abu Said, and removed the stone from the dead man’s clothing.

Regrettably for Don Pedro, in 1366 he found himself in the middle of a civil war and needed help. He turned to England and Edward of Woodstock, son of Edward the III and known as “The Black Prince”. Edward struck a hard bargain: he demanded the ruby in exchange for military aid. He took the stone back to England, and added it to the Crown Jewel collection. In 1415, King Henry V had the stone mounted on his war helmet, and wore it to the Battle of Agincourt – whether it was vanity or common sense, the jewel saved Henry’s life. He was struck by an axe and, though wounded (and his helmet destroyed), the stone deflected the blow. Both Henry and the stone survived. There are tales of other English royalty wearing the Ruby into battle as well, however, they did not fare as well as Henry and died in combat. In 1649, the Ruby disappeared. Some speculate that it had been sold – for a mere four pounds! – but in any case, it resurfaced about a decade later, as the Restoration was getting underway. The Ruby was mounted on the top of the Crown; when the Crown was re-designed for Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838, the Ruby – by now known to be a Spinel – was mounted at the front.

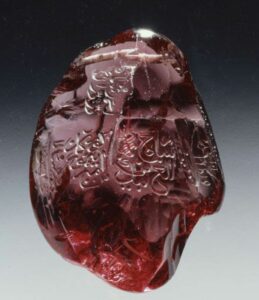

The highly historic – and colossal – Timur Ruby is a 352.50-carat spinel that is now the centerpiece of an opulent necklace in Queen Elizabeth’s personal jewel collection. Also known as Khiraj-i-alam, or ‘Tribute to the World’, we first hear about this stone in the 14th century. Named for Tamerlane the Conqueror, who allegedly discovered the stone while capturing and looting Delhi, the Timur Ruby is engraved with names and dates of six Moghul emperors – not all of whom actually owned the stone. Emperor Jahangir said of his own inscription, “This jewel will more certainly hand down my name to posterity than any written history. The House of Timur may fall, but as long as there is a King, this jewel will be his.” Another emperor, Farrukhsiyar, engraved the stone, not with his name but with this rather lengthy description: “This is the ruby from among the 25,000 authentic jewels of the King of Kings, the Sultan Sahib Qiran [Tamerlane], which in the year 1153 [1740 AD] from the jewels of Hindustan reached this place [Isfahan].”

In 1739, the Shah of Iran, Nader Shah, occupied Delhi. He agreed to withdraw from the city if given the keys to the Royal Treasury, which held not only the Timur Ruby but also the huge Koh-i-Noor and Darya-ye-Noor diamonds and the gem-encrusted Peacock Throne. Nader Shah was assassinated in 1747 and both the Timur Ruby and the Koh-i-Noor Diamond ended up with Ahmad Shah Durrani (considered the founder of modern Afghanistan). Ahmad Shah was the last person to engrave his name on the stone, but apparently even the huge Timur Ruby was getting a bit crowded, as Ahmad Shah erased the inscription allegedly engraved by Tamerlane himself.

The Timur Ruby continued to move with emperors as their kingdoms waxed and waned. Ahmad Shah’s grandson was forced into exile in Punjab, India where he was required to give up the jewels to Maharaja Ranjit Singh (founder of the Sikh Empire). But, the British East India Company was on the rise; annexing the Punjab in 1849, it also took possession of all the State jewels.

In 1851, the Company presented a collection of jewels, including the Timur Ruby, to Queen Victoria; in 1853, the stone was mounted into a stunning necklace, with the giant spinel as the central pendant amongst fine diamonds. Interestingly, the necklace has never been worn.

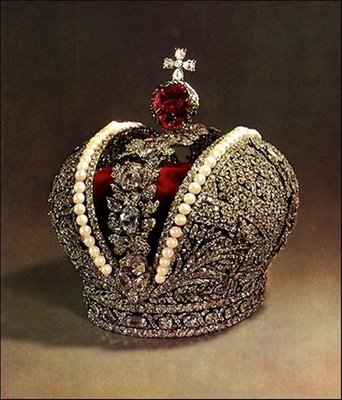

At 398.72 carats – nearly 80 grams – Catherine the Great’s Ruby is believed to be the second-largest spinel in the world. Brought to Russia by Nicholas Spafary, who was the Russian envoy to China in the late 1700s, the Spinel is mounted amidst 4,963 diamonds in the Great Imperial Crown which, incidentally, weighs nine pounds. This spinel is considered one of the seven historic stones of the Russian Great Stone Collection within the Russian Crown Jewels.

The Crown’s last appearance at a coronation was that of Nicholas II in 1896, though it was also present at the State Opening of the Duma in 1906. This fabulous Crown – with its massive red spinel – is now on display in the Moscow Kremlin Armory State Diamond Fund

The dazzling and dizzying array of precious stones in the Iranian Crown Jewels collection includes the world’s largest known spinel: the gargantuan, blood-red Samarian Spinel weighs in at 500 carats. The stone was taken from India, along with a slightly less extravagant 270-carat spinel, by Nadir Shah of Persia. The smaller spinel, like so many other gemstones that came into his possession, is engraved with the name of Emperor Jahangir.

However, the Samarian Spinel, while inscription-free, has a more curious story: there is a hole in it. This aperture is allegedly described by Nassereddin Shah Qajar, the 19th-century Persian king, as made in order to hang the stone around the neck of the biblical Golden Calf, produced by the impatient Israelites while Moses was receiving the Ten Commandments. Unfortunately, there is no way to confirm this tale. A diamond was mounted to cover the hole, but it is no longer on the Samarian Spinel.

Moving from mammoth to merely spectacular, the French Crown Jewels boast one of the most charming spinels known: The Côte-de-Bretagne. Thought to date back to at least 1530, and mistaken for a ruby for centuries, the jewel is a 105-carat orange-red stone carved into the shape of a fat “Oriental” dragon. It was originally mounted in the magnificent rococo-style Insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece, along with what is now the famous Hope Diamond (formerly the French Blue). Now on display at the Louvre in Paris, the Côte-de-Bretagne is believed to be one of very few spinels in the collection, as well as one of the oldest pieces and definitely among the most recognized.

During the French Revolution, most of the French Crown Jewels were stolen from the Royal Storehouse (the Garde-Meuble) over a five-night period. One of the thieves absconded with the Golden Fleece Insignia, unmounting both the Côte-de-Bretagne and the French Blue from their setting. He fled to London, where most of the stolen loot was sold. Although many of the gems were never recovered, miraculously, in 1797, the Côte de Bretagne spinel surfaced in London, and was restored to the French Crown Jewels collection.

The spinel, rarer than the ruby and with more colors than the rainbow, has possibly adorned more of history’s powerful, charismatic men and women than any other gemstone. It is only fitting. After all, the spinel is itself powerful and strong, casting a bedazzling spell on any human being fortunate enough to even glimpse one of these natural wonders.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timur_ruby

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samarian_spinel

- http://famousdiamonds.tripod.com/samarianspinel.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spinel

- https://books.google.co.th/books?id=hKYPZGm37hMC&pg=PA153&lpg=PA153&dq=tamerlane+spinel&source=bl&ots=xQRlHnbs0g&sig=TKdenKaTbEpTnSQw4wfHbXkPaCg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi7–Pn3d3MAhUKuo8KHUQFDFwQ6AEIMjAE#v=onepage&q=tamerlane%20spinel&f=false

- http://www.ganoksin.com/borisat/nenam/afghanistan-rubies-spinels.htm

- http://www.lotusgemology.com/index.php/library/articles/155-spinel-resurrection-of-a-classic-gem

- http://observer.com/2015/09/a-historic-arcane-red-gem-makes-auction-history/

- http://www.nrl.navy.mil/media/news-releases/2015/transparent-armor-from-nrl-spinel-could-also-ruggedize-your-smart-phone

- http://www.mindat.org/min-3729.html

- http://www.minerals.net/gemstone/spinel_gemstone.aspx

- http://geology.com/minerals/spinel.shtml

- https://www.gemrockauctions.com/learn/additional-gemstone-information/mahenge-spinel-the-stone-that-changed-everything

- http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/jewelry/an-imperial-mughal-spinel-necklace-5436541-details.aspx

- http://noospheregeologic.com/blog/2012/09/12/the-rare-gem-series-spinel-the-balas-ruby/

- http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/arts/13iht-acaj-spinel-jewelry13.html?_r=0

- http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O16068/the-carew-spinel-spinel-unknown/

- http://www.palagems.com/spinel-ball/

- http://www.ruby-sapphire.com/r-s-bk-quality5.htm#Table_10.4

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Crown_of_Russia